Menu

Menu

A Sonic Modesty

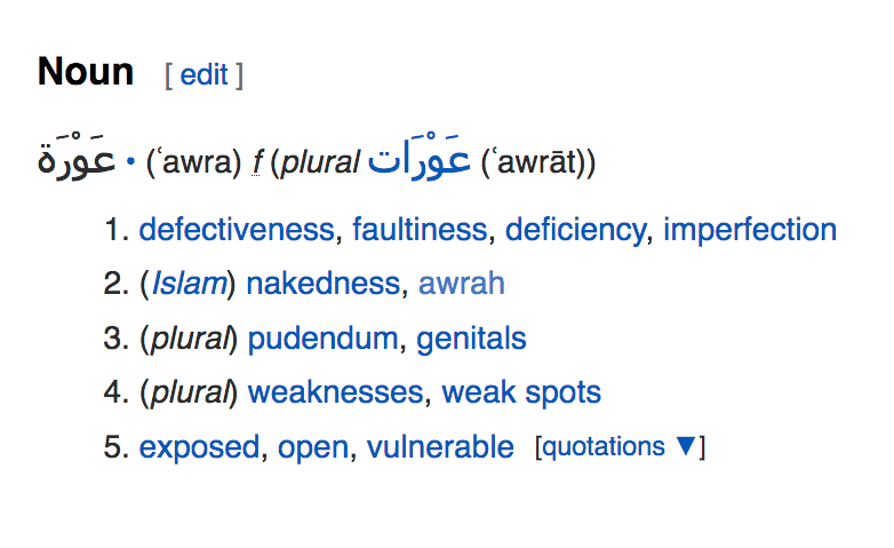

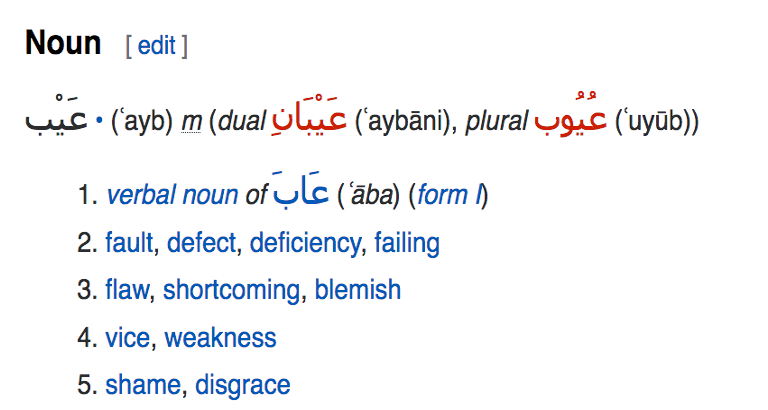

One word that Pope Shenouda III used to describes the mixing of men and women’s voices in worship was ’ayb or “shame.” It is a familiar word to many Egyptian and Coptic women, and one that is often used to describe women’s modesty and honour. It has also been regularly used to shape, bolster, and monitor women’s comportment in public and private contexts, including their singing participation in the Orthodox Church.

The word ‘ayb also mirrors the widely understood notion of “’awra” to describe women’s voices in sacral contexts. Unlike men’s voices, women’s voices are understood to carry sexual connotations— “’awra” literally means women’s pudenda or privates— and are believed to have the potential to corrupt public morals (Badran 1995: 16)—something that Pope Shenouda mentioned in his sermon. This may explain the dialectical and at times contradicting understandings of the role of women in the Coptic Church: the very same bodies whose sexuality and presence carries disruptive potentialities also have potentially life-giving abilities to produce the next generation of Copts. It is with this ambivalence that Coptic women are widely celebrated as mothers, and motherhood is highly venerated within the community, with deep expectations for women to marry within their communities and to reproduce the next generation of Copts.

Singing as a Coptic woman is further complicated by the Coptic community’s experiences of systemic religious discrimination in Egypt. Rising sectarian tensions as well as a crumbling economy have prompted many Copts to leave, alongside a smaller number of their Muslim kin. Yet, even as Copts immigrate, memories of sectarian violence, marginalization, and even death as a religious minority have shaped diasporic theologies focused on martyrdom, obedience, and survival (Youssef 2020). These theologies, while focused on preserving religious practice and community boundaries, have had significant ramification for women whose subordination, modesty, strict gender norms, and silences are seen as conditions to survival in the diaspora. Gender studies scholar Mariam Youssef writes: “The identity of martyrdom has been a source of inspiration for many Copts and encourage them to remain resilient in the face of persecution, but it is also used to silence women who express dissatisfaction with their lack of liturgical roles and visibility.” (2020:18).

Copts not only assimilate to these theologies of survival through martyrological films, Sunday school lessons, celebrations of the Coptic calendar around their feast days (designated AM: Anno Martyrum), but also through ubiquitous references to these saints in spiritual song and liturgical hymns. References often celebrate historical martyrs alongside victims of contemporary sectarian violence, elevating their death as the ultimate sacrifice for the Coptic church as the “Bride of Christ”—the same metaphor that is drawn on the bodies of little girls when they are dressed as little brides after their baptismal rites. In many ways, while women may not always be able to openly or loudly sing in the Coptic Church, the community’s minority politics are already written, sung, and performed on and through their bodies.

The word ‘ayb also mirrors the widely understood notion of “’awra” to describe women’s voices in sacral contexts. Unlike men’s voices, women’s voices are understood to carry sexual connotations— “’awra” literally means women’s pudenda or privates— and are believed to have the potential to corrupt public morals (Badran 1995: 16)—something that Pope Shenouda mentioned in his sermon. This may explain the dialectical and at times contradicting understandings of the role of women in the Coptic Church: the very same bodies whose sexuality and presence carries disruptive potentialities also have potentially life-giving abilities to produce the next generation of Copts. It is with this ambivalence that Coptic women are widely celebrated as mothers, and motherhood is highly venerated within the community, with deep expectations for women to marry within their communities and to reproduce the next generation of Copts.

Singing as a Coptic woman is further complicated by the Coptic community’s experiences of systemic religious discrimination in Egypt. Rising sectarian tensions as well as a crumbling economy have prompted many Copts to leave, alongside a smaller number of their Muslim kin. Yet, even as Copts immigrate, memories of sectarian violence, marginalization, and even death as a religious minority have shaped diasporic theologies focused on martyrdom, obedience, and survival (Youssef 2020). These theologies, while focused on preserving religious practice and community boundaries, have had significant ramification for women whose subordination, modesty, strict gender norms, and silences are seen as conditions to survival in the diaspora. Gender studies scholar Mariam Youssef writes: “The identity of martyrdom has been a source of inspiration for many Copts and encourage them to remain resilient in the face of persecution, but it is also used to silence women who express dissatisfaction with their lack of liturgical roles and visibility.” (2020:18).

Copts not only assimilate to these theologies of survival through martyrological films, Sunday school lessons, celebrations of the Coptic calendar around their feast days (designated AM: Anno Martyrum), but also through ubiquitous references to these saints in spiritual song and liturgical hymns. References often celebrate historical martyrs alongside victims of contemporary sectarian violence, elevating their death as the ultimate sacrifice for the Coptic church as the “Bride of Christ”—the same metaphor that is drawn on the bodies of little girls when they are dressed as little brides after their baptismal rites. In many ways, while women may not always be able to openly or loudly sing in the Coptic Church, the community’s minority politics are already written, sung, and performed on and through their bodies.

Mariam Youssef leads St. John’s ecclesiastical choir through the centre of the Church. Since its inception in 2004, the choir has changed significantly, with younger and younger members joining. The change highlights a challenging dynamic of the choir; while the ecclesiastical forges an important auditory space for Orthodox women, this space also had disciplinary intentions, namely for church clergy to encourage women to attend service and “to dress appropriately in a special uniform that conforms to the ethics and spirit of the Church.” After 15 years of service, Mariam has since left the choir. Photo courtesy of Mariam Youssef.

One of the most familiar Arabic words to Egyptian and Coptic women is ‘ayb or “shame.” The term often guides proper comportment in public spaces, including what women wear, how loud they laugh, or if they sing too loudly in a Coptic Church. In Egyptian as well as Middle Eastern culture more broadly, women’s voices are believed to have transgressive potential to corrupt public morals; feminist activists are pushing back against the double standards of the term.

Previous

Next

Side by side, Wikipedia’s open-sourced entries on ‘ayb and ‘awra highlight the gendered interpolation of the term “shame” with a women’s “privates” in the Arabic speaking world. It also showcases how issues of respectability and sexuality are deeply bound up in women’s voices, with deep efforts to “veil” and limits women’s audibility in sacred contexts, such as Coptic Church liturgical services. Screenshots by the author.