Menu

Menu

Singing a Coptic Afterlife

For Orthodox Copts, there is a widely held understanding and comfort that the life after this one is not alone nor is it quiet. Rather, the afterlife—reserved for holy lives, holy saints, and those who die holy deaths as martyrs for their faith— is conceived as an eternity spent in the sounded divinity of God. In other words, this heavenly state is known as tasbīḥ or the Arabic term for sounded praise. On earth, tasbīḥ consumes Coptic life as Copts sing to secure their place in eternity. The Coptic Orthodox liturgy is the weekly—and for some parishioners, monks, and nuns, the daily—recapitulations of heaven on earth, as parishioners consume the Body (Bread) and Blood (wine) of Christ in the most venerated and intimate act of Communion. In turn, the Eucharist or al-tanāwil, binds Copts to one another, to their community, and to a sense of a heavenly belonging that is central to what the previous Coptic patriarch, Pope Shenouda III, called a “heavenly citizenship” to a “heavenly nation.”

This should explain why the Coptic liturgy is so highly venerated, even fiercely guarded against any changes except for the translation of liturgical texts from Coptic into Arabic, and then, the new languages of the diaspora. Importantly, it also explains why a gendered participation is heavily conscripted and choreographed between a male priest (an abūna), male cantors (p. shamamsa, s. shamās), and a mixed congregation (sha’b). In this intimate contrapuntal exchange, participants feeds each other their musical lines in an oral performance that typically lasts between 3 and 4 hours. There is no written notation with the exception of what participants use to learn the hymns outside of the service. Rather, the entire community collectively remembers and performs the liturgy together. And, they do so through regular attendance once, if not several times a week.

This should explain why the Coptic liturgy is so highly venerated, even fiercely guarded against any changes except for the translation of liturgical texts from Coptic into Arabic, and then, the new languages of the diaspora. Importantly, it also explains why a gendered participation is heavily conscripted and choreographed between a male priest (an abūna), male cantors (p. shamamsa, s. shamās), and a mixed congregation (sha’b). In this intimate contrapuntal exchange, participants feeds each other their musical lines in an oral performance that typically lasts between 3 and 4 hours. There is no written notation with the exception of what participants use to learn the hymns outside of the service. Rather, the entire community collectively remembers and performs the liturgy together. And, they do so through regular attendance once, if not several times a week.

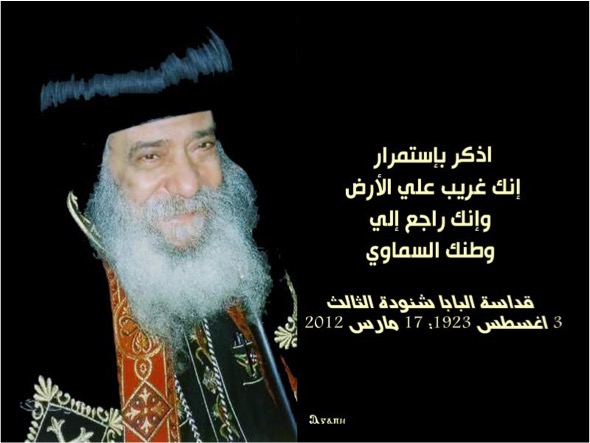

The previous Coptic patriarch, Pope Shenouda III (1923 – 2012) deeply shaped contemporary religious culture through his writing, sermons, and poetry turned into vernacular spiritual songs (taratīl). His teaching often emphasized an eschatological and ascetic dimension of Coptic spirituality. The translation of this meme is “Remember always that you are a stranger on earth and that you will return to your heavenly nation.” Many of his songs have also been translated into English. Listen to the St. Bishoy and St. Shenouda’s youth in Australia presents Pope Shenouda’s poem Stranger / Al-Gharīb.