ESSAY:

Stereo to Mono

As American Religious Sounds Project researchers, we’ve typically experienced religion in stereo: we’ve been surrounded by the many sounds of religious communities and events – singing, chanting, laughter, cooking, dancing – that combine to form dynamic audio waveforms for recording.

The pandemic changed this. Along with much of the world, we found ourselves sequestered at home and reliant on computers for daily life activities, including conducting audio fieldwork. The sounds of religion – once richly layered and multi-directional – became audibly flat as they were compressed and funneled through tinny speakers (and subject to the whims of unstable internet connections). As we listened, fundamentally “stereo” sounds suddenly became “mono” ones.

What happens when religious sound is flattened in this way – when it loses its in-person dimensionality? And does flattening religious sound necessarily flatten religious experience?

These and other similar questions came to mind as we launched the ARSP COVID initiative, which eventually elicited more than 150 crowdsourced recordings from across the country that documented religious sound during the pandemic. The majority of these recordings depicted online worship services and gatherings, and some came from communities and events we had recorded in-person prior to COVID-19. Listening to the communities now, the difference in religious practice and experience is audible.

For members of the Winding Road Coven, a Wiccan community in central Ohio, the shift to “mono” religious sound made some traditional practices unfeasible. Prior to the pandemic, coven members regularly performed the Cone of Power, a ritual designed to generate and channel energy for magical purposes. Participants would stand in a circle, lock hands, and each chant selected phrases at a slightly staggered pace, together weaving an energetic aural tapestry. During the pandemic, with participants chanting remotely on their individual devices, the tapestry started to unravel. Compression and connectivity issues caused voices to break, jutter, and interrupt each other. “This isn’t going to work,” a woman says in the recording below, shortly before the priest asks everyone to mute themselves. The Cone of Power is effectively silenced.

The Winding Road Coven Cone of Power ritual in December 2018. Photograph by Lauren Pond.

Members of the Winding Road Coven participate in a Cone of Power ritual in person in 2018, followed by a recording of the Cone of Power ritual performed on Zoom in 2020. Recordings by Lauren Pond.

Top: The singing bowl circle in Whetstone Park in 2017. Photograph by Lauren Pond. Bottom: The online soundbath meditation in 2020. Screenshot by Amy DeRogatis.

A singing bowl circle in Columbus in 2017, followed by a recording of an online soundbath meditation in 2020. Recordings by Lauren Pond and Amy DeRogatis.

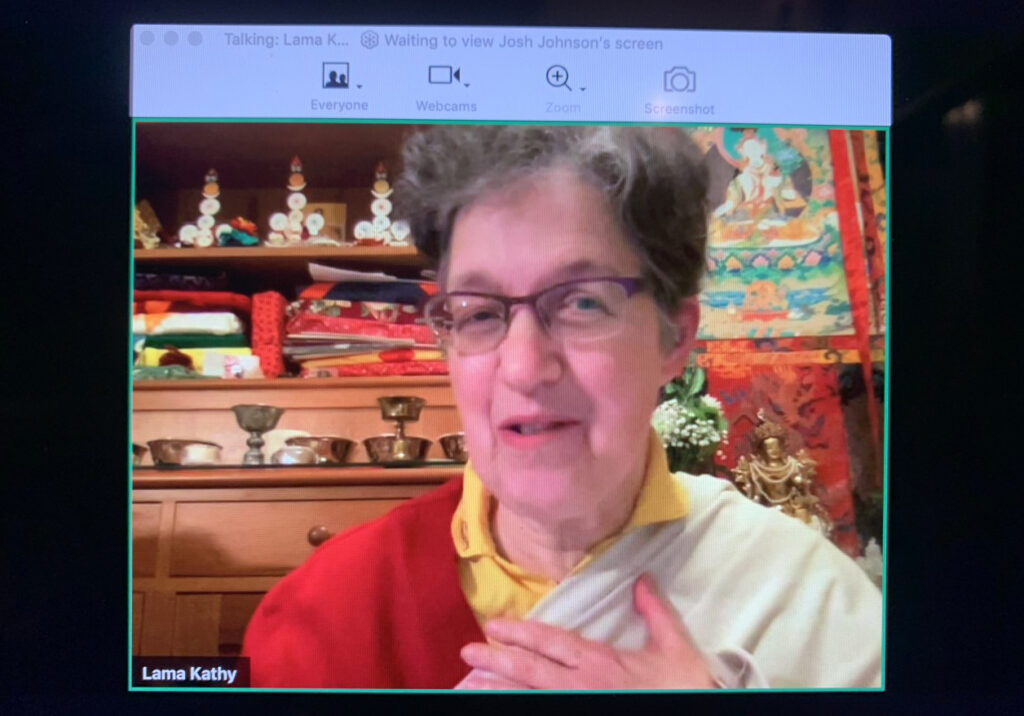

Top: The in-person Interfaith Memorial for the Homeless in 2015. Photograph by Isaac Weiner. Bottom: Lama Kathy of the Columbus Karma Thegsum Choling center speaks during the online memorial in 2020. Screenshot by Lauren Pond.

An in-person Interfaith Memorial for the Homeless in 2015, followed by a recording of the memorial online in 2020. Recordings by Isaac Weiner and Lauren Pond.

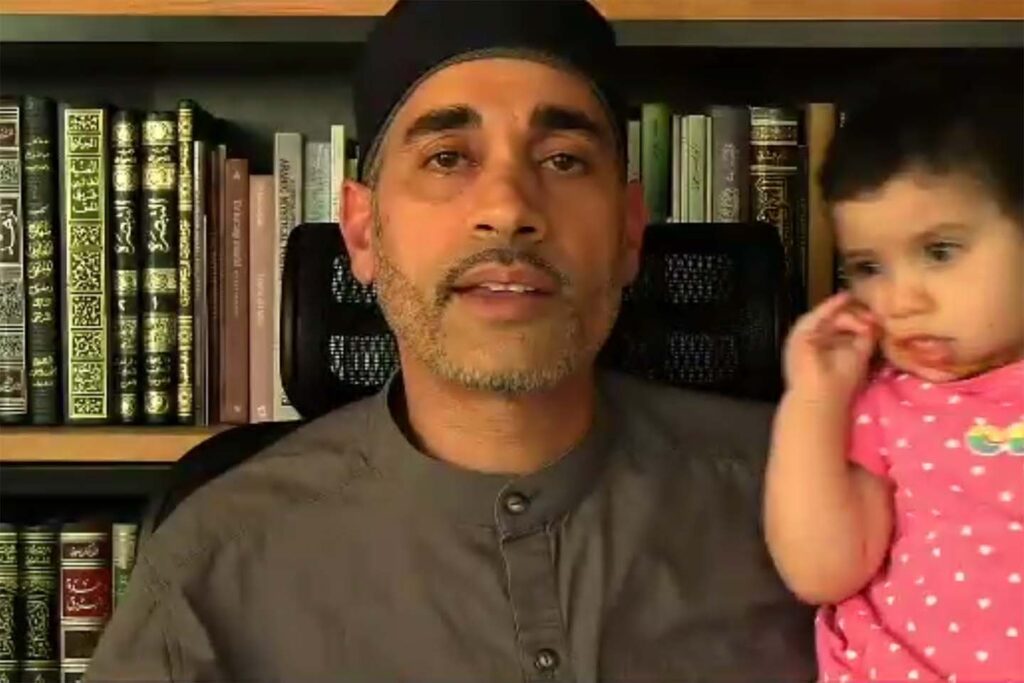

For yet other communities, participating in “mono” religious practices at home has created a new kind of stereo audio waveform – one that combines the tracks of religious and domestic life. In many of the crowdsourced audio recording submissions we received, contextual ambient sounds seep in and complement the sounds of an online worship service or other religious event. Below, the sounds of New Yorkers cheering for first responders are audible alongside the sounds of a Zen Buddhist chanting in Pali during an online sangha, and the vocalizations of a young child interrupt a Muslim imam as he speaks about the teachings of the Qur’an during an online meeting.

A Muslim imam and his child during an online Qur’anic discussion in 2020. Screenshot by Garrett Gaines.

A woman participates in online Zen Buddhist chanting while the sounds of people chanting for first responders are audible outside of her New York City apartment window. Recording by Elizabeth Kineke.

A Muslim imam attempts to discuss the Qur’an and its teachings online as his child makes noise in the background. Recording by Garrett Gaines.

Similar to some of our pre-pandemic recordings, religious sound extends beyond the walls of houses of worship, and pandemic religious sound invites us to witness the frequent yet perhaps unexpected intersections of the sacred with the everyday. It expands our understanding of what religion is and where it can be found.

Listening through these and other COVID audio submissions, it becomes clear that although recordings are compressed and tinny, for communities, “flat” sound has actually been quite dynamic. For some, it has wreaked havoc on religious experience and interpersonal connection. For others, it has generated new opportunities and meaning. For all, it has brought change. While many communities have now resumed in-person gatherings and are once more experiencing religion in “stereo,” the pandemic is far from over, and the effects of these changes are likely to be felt for years to come.

– Lauren Pond