ESSAY:

Religious Tourism during COVID

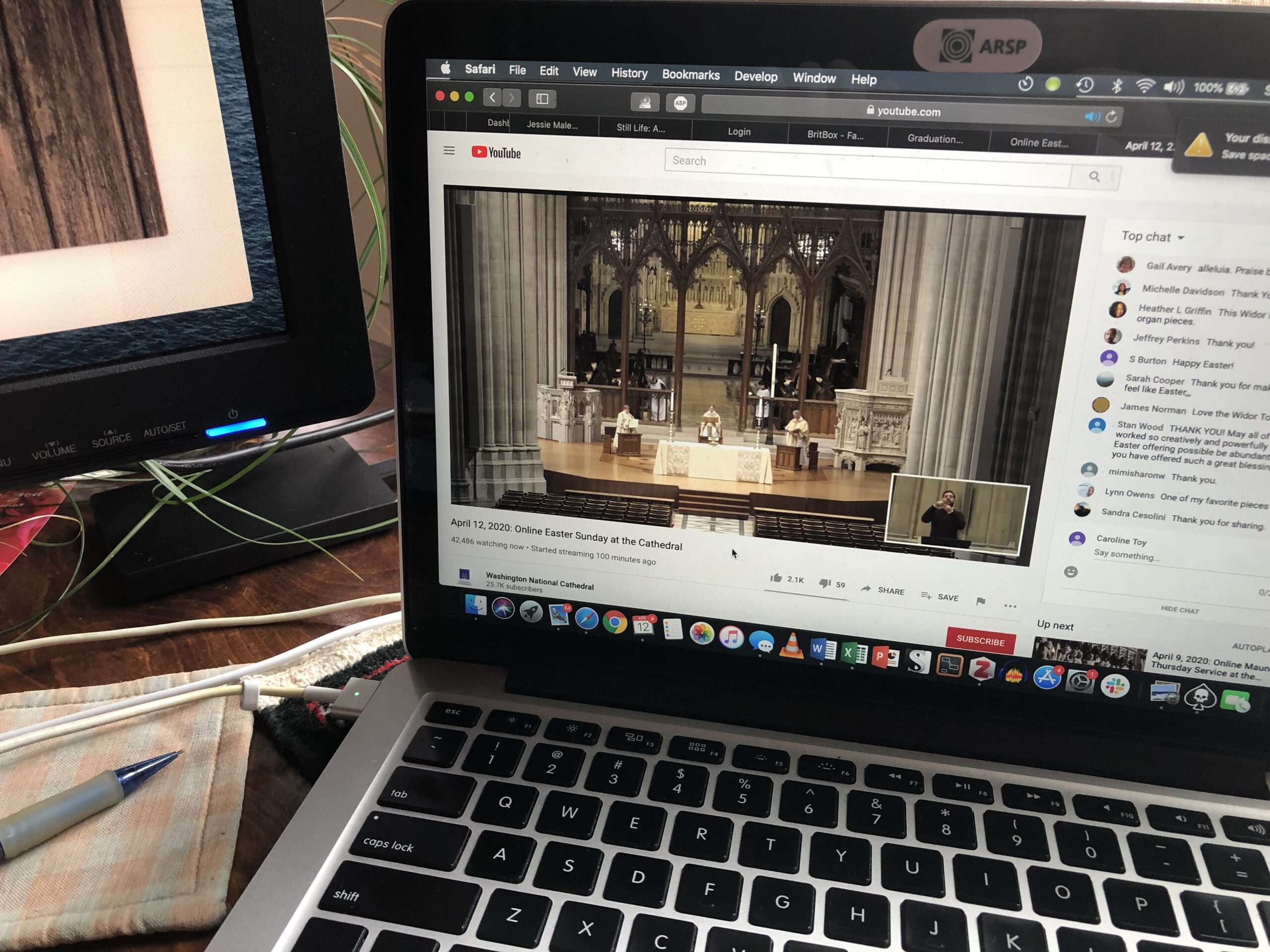

COVID-19 and its associated quarantine measures not only changed how people practiced religion; it also changed where they practiced and with whom. In the materials people submitted to our project, it wasn’t uncommon for people to celebrate with communities where they didn’t typically participate. This map shows a snapshot of only a few of these examples: people from multiple locations participating in worship at Central Synagogue in New York, a woman in Vermont listening to the Easter service live stream from the National Cathedral in Washington, DC, a woman in Spokane, WA listening to a calligraphy lesson in the UK. [Explore the points on the map to see/hear other examples. On smaller screens you may need to scroll left or right to see all the points.]

Washington DC

, on Fox News (Washington DC), recorded on March 29 2020 by Skylar Berlin in Rockford MI

at Washington National Cathedral, recorded on April 12 2020 by Caroline Toy in Colchester Vermont

Massachusetts

of Catedral de Adoracao - Igreja Brasileira em Boston, recorded on April 12 2020 by Amy DeRogatis in East Lansing MI

at Emmanuel Church in Boston MA, recorded on April 12 2020 by Skylar Berlin in East Lansing MI

Michigan

, on Fox News (Washington DC), recorded on March 29 2020 by Skylar Berlin in Rockford MI

in the Bay Area, recorded on April 11 2020 by Skylar Berlin in East Lansing MI

of Catedral de Adoracao - Igreja Brasileira em Boston, recorded on April 12 2020 by Amy DeRogatis in East Lansing MI

at Emmanuel Church in Boston MA, recorded on April 12 2020 by Skylar Berlin in East Lansing MI

at Central Synagogue in NYC, recorded on April 25 2020 by Skylar Berlin in East Lansing MI

New York

at Central Synagogue in NYC, recorded on April 25 2020 by Skylar Berlin in East Lansing MI

as part of Virtual Ramadan at NYU, recorded on May 11 2020 by an anonymous contributor in Issaquah WA

from Central Synagogue in NYC, recorded on April 9 2020 by Sophie Davies in Bodenham UK

Russia

from the Islamic Center of Orange County CA, recorded on May 8 2020 by an anonymous contributor in Russia (precise location unknown)

Southern California

from the Islamic Center of Orange County CA, recorded on May 8 2020 by an anonymous contributor in Russia (precise location unknown)

Texas

, on Fox News (Washington DC), recorded on March 29 2020 by Skylar Berlin in Rockford MI

United Kingdom

from Central Synagogue in NYC, recorded on April 9 2020 by Sophie Davies in Bodenham UK

at Cambridge (UK) Muslim College, recorded on May 3 2020 by an anonymous contributor in Spokane WA

at Washington National Cathedral, recorded on April 12 2020 by Caroline Toy in Colchester Vermont

at Cambridge (UK) Muslim College, recorded on May 3 2020 by an anonymous contributor in Spokane WA

as part of Virtual Ramadan at NYU, recorded on May 11 2020 by an anonymous contributor in Issaquah WA

We made the specific choice to center the listener on this map. True, the Washington National Cathedral and Central Synagogue and other religious organizations are broadcasting out, but at the same time they have no idea who – if anyone – is going to tune in. They are simply putting these sounds out into the universe, and it is up to the listener to go out and find it. Therefore on our map, on the lines connecting the listener to the thing-listened-to, the arrows indicate the direction of the listening. An arrow out from the site of a broadcast would imply that, for instance, was being done for the specific benefit of a person in Issaqah, WA, rather than that person in Washington reaching out to find the recording from NYU. In cases like , there was reciprocal listening between Osteen in Houston and host Chris Wallace, but one-directional listening from recordist Skylar Berlin (in Rockford, MI) to the two men.

Despite their invisibility, however, those intervening nodes are audible, often through interruption or interference. The distortion in the recordings of the and the were introduced as those sounds were compressed, moved between online nodes, and played through tinny laptop speakers. Even when all participants were in relatively close physical proximity, as in the Winding Road Coven cone of power Lauren Pond discusses in her essay, the lag introduced by virtual “hops” around the country transformed the practice from unified to disjointed.

By complicating the question of where these religious practices were taking place, these recordings also troubled the very idea of American religious sounds. We chose the most inclusive approach, wherein if any portion of the network existed within North America, the sound could be considered “American.” Thus, for our purposes, the recording of the (recorded from Russia) was considered an American religious sound, but so too was the recording of a at Cambridge Muslim College in the UK, because of the listener’s position in the US.

Beyond its implications for our particular project, COVID should make us reconsider how we think about sound and religion in general, as well as how we practice religion post-pandemic. How much practice will remain online? Will religious groups expand how they think about “community,” to incorporate virtual as well as physical space in a way that mimics other online communities? Will they grow beyond geographic borders, or become more Balkanized, drawing in only those who specifically seek them out, or both? Which religious practices will have their sounds amplified online, which will become distorted through the change of medium, and which will be silenced altogether?

– Alison Furlong